Litchfield County, CT

November 2, 2007

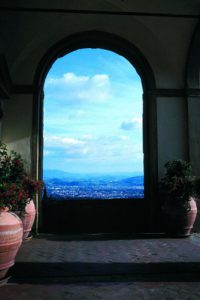

Portrait by Randy Clark.

WASHINGTON-In the old barn behind Elizabeth Richebourg Rea’s blue house in Washington a series of photographs wraps around the walls in a horizontal band. Encased in plain black frames, they shine through their glass barriers and cast a twinkle on the room. Together, they represent Ms. Rea’s oeuvre.

Natural Light

In one, a friend scratches her dog’s ears, the woman’s crinkled, smiling face and the dog’s rolls of fur filling thc entire frame. The images are large, measuring nearly three feet by two feet and the subjects have an commanding presence in the room, as though they are there and larger than life. Each one is filled with a dramatic sweep of emotion and scale.

Using only natural light, Ms. Rea frames the compositions with an arresting tension—bodies are often cropped and lush landscapes have a sense of emptiness. Black shadows drape over settings and contrast with the ethereal glow of white that leads the eye around the composition.

Taken of friends, family and strangers—”it really doesn’t matter who they are,” she said—the photographs reveal the depth of everyday moments, which can be a clear expression of joy or, more often in her work, that of loss. Each image is seen through a lens heavy with the sadness of the fleeting nature of a moment, but also celebratory of each moment’s very existence.

The images may surprise those who are more familiar with Ms. Rea as the widow of Michael M. Rea and the director of the Dungannon Foundation, which annually administers The Rea Award for The Short Story, given to an American or Canadian writer who has made significant contributions to the genre.

Since her husband’s death in 1996, Ms. Rea has devoted her time to “putting out fires” and fulfilling a “tremendous promise” to continue his work in the arts, including being a member of the Art and Museum Committee at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Now that the 20th Anniversary Celebration of the Rea award and being honored at Symphony Space in New York City have passed, Ms. Rea has had time to refocus on her photography and has learned how to handle her role in maintaining her husband’s legacy.

“I feel more comfortable with it,” she said. “Maybe it’s time now to come out.”

Twelve of her newest photographs taken since 2004 will be on display at Litchfield’s New Arts Gallery beginning Nov. 10 in a four-person show entitled, “IMAGE,” that will run through Dec. 10. Ms. Rea is the only Litchfield County photographer in the show, which gallery owner Tony Carretta described as being “about the medium of photography, but the content is about ‘image-making’ without the restraints of tradition.”

When Mr. Carretta first encountered Ms. Rea’s work several years ago, he was struck by the “theatrical” quality of it and compares her not to other photographers but to filmmakers Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, “who understand the value of portraying a moment or sequence of moments that mark time or experience but through the lens of personal vision.” Her work is being presented alongside that of New York Cily artists Peter Angelo Simon and Manuel Geerinck and Norwegian artist Tone Fogth.

“I do feel that I am telling a story often and that I am part of that tale, whether it be just as a private eye, if you will, or as part of the dilemma, or the experience,” the photographer explained. “Of course, all photography is somehow about the photographer, who takes part in the moment of the shot: self portraits in a way.”

“IMAGE” features Ms. Rea’s latest exploration of landscapes as well as her portrait work, which will be seen for the first time. In her landscapes, she incorporates the human form into the scene by forgoing the subjects obvious humanity—faces, close-updetails—in favor of silhouettes that express a mood. In landscapes without human subjects, the signs of a now-gone human presence exist. A small light flickers in the background and a lawn is perfectly manicured. “And how did that land get so manicured?” she asks herself.

Using a Leica M6 manual camera or the new M8 digital version, she shoots evening photographs with daylight film. Ms. Rea prints exclusively on Ilfochrome Classic (formerly Cibachrome), a color print material that eliminates internegatives. This choice means photographs with rich, saturated colors that are sharper—the dyes are in the paper and do not bleed—and a shiny, glass-like finish on the plastic, which lends to the cinematic quality of her work. It can take up to a year for her to see the final product because of her editing and printing styles.

Ms. Rea first studied photography in 1993 when she took classes at the International Center of Photography in New York City, and then in Santa Fe. She counts as an influence New York City photographer Garry Winogrand, a noted street photographer who captured the gritty realism of American life in the middle of the 20th century. Her formal education is in art history, having graduated from Principia College in Illinois in 1969. “My real love is traveling and museums and seeing the original influence,” she said.

From there, she began a formidable career in the museum and gallery world, at one point co-owning the Richebourg/McCoy Gallery in New York City. “I got a job at the Museum of Modem Art because I could type,” she said of her post-college foray into the art scene. That typing job turned into a position in the early 1970s running the Art Lending Service and Art Advisory Service for Penthouse Exhibitions.

After that, she went to work at the Leo Castelli Gallery, which showed Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol. While there, she represented the estate of Joseph Cornell, an American artist and sculptor famous for his assemblage work, and staged an exhibition of his works in 1978.

Ms. Rea would revisit Cornell’s work in an unexpected way nearly 30 years later when she staged ashow at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Fla., where her husband had been a trustee. Rea had only recently passed away but she forged on to do the show. It was something, she said, she had to do for fear of letting down her husband.

The show provided a distraction for Ms. Rea, and in 1997 her own work was on display at the Washington Art Association with Jeannette Montgomery Barron and Carrie Coco. “He. loved my photography,” Ms. Rea said of her late husband, knowing that he would want her to continue with her work.

An appearance at the New Arts Gallery in 2002 garnered praise in the local press. Alistair Highet wrote in the Hartford Advocate, “There’s an eerie, suspended anxiety that runs throughout the pictures—as though the death of every moment that photographer captures has been insufficiently grieved ….” Tracey O’Shaughnessy of the Waterbury Republican-American noted, “Rea captures [burgeoning femininity in young girls] with an electric enthusiasm, blessedly devoid of irony.”

Despite her occasional shows, Ms. Rea’s work remained under the radar for the public following her husband’s death. The onus of running The Dungannon Foundation required all of her attention. “The Rea Award wasn’t my area. … He was the reader. He got the jurors.” She was also steadfast about maintaining Rea’s traditions, including attending the ceremonial luncheon with the jurors and personally making the call to the winner. It is a complicated role for Ms. Rea, who is admittedly happiest when she is working on her photography.

“There is a relationship to hiding behind something,” she said, whether it is “hiding” behind her camera or behind the award. “I do feel a responsibility to Michael’s legacy in running the Dungannon Foundation, but thankfully this past year is behind me … Now, however, it is an ‘annual’ venture that I take great pride in managing; it is not a full-time job.”

Yet returning to her photography with more focus does not diminish that to which she has devoted the last decade of her life. “It can only broaden the horizon, expand the experience; I have learned about a new world, an inspiring one and one that actually ‘fits’ with my work, the narrative aspect of it, especially the moody, emotional experience I draw from in my daily life and now, from stories and from writers I’ve met in the world of literature. I view it as another world to explore, first with my husband, and now on my own. I do have my camera with me for the jurors’ meetings; in the end, it is all about people, their venue, the intimate landscapes involved in my life,” she said.

When “IMAGE” opens in one week, the presence of Rea and the photographer’s experiences will be on display. Ms. Rea keeps no photo albums documenting her life, only the images she creates through her art. The Reas loved to travel during their marriage and toured 14th-century Romanesque churches; “Altar in Asolo II” (2004) reflects that influence. In the future, she would like to work on books centered on a theme, perhaps one on those churches she photographed while traveling with Rea. Finding representation at a New York City gallery is also of interest.

The New Arts Gallery in Litchfield will host an opening reception for “IMAGE” and its artists Saturday, Nov. 10, from 3 to 6 p.m. For more information on “IMAGE” call the gallery at 860-567-5015 or visit its Web site at www.newartsgallery.com. Elizabeth Richebourg Rea’s Web site is www.elizabethreaphotography.com.